Rewind: Work that does not pay, the double burden women bear

When it’s domestic work, it’s a women’s job, and their external employment hardly matters as even there, the compensation is gender-linked

Published Date – 17 May 2025, 11:16 PM

By Avani Thatte, Sharmi Das, Gummadi Sridevi

Unpaid work is mostly seen as work outside the realm of economic activity and often goes unaccounted for in the national income accounts. Since the late 1960s, feminist economists have been advocating for the inclusion of unpaid work within the economic framework just as paid work.

In recent years, there has been a growing number of studies that discuss the burden of unpaid work women have to bear. Academic Indira Hirway questions the arbitrary division and separation of the economy into productive and reproductive activities and argues that macroeconomic policies cannot be made in isolation without taking into account the non-System of National Accounts (non-SNA) activities as productive as these activities are interconnected. (Nandi, 2019). Estimates suggest unpaid care and domestic work will account for 39 per cent of India’s GDP.

Caregiving is a huge component of unpaid domestic work done by women at home. As India is on the path to becoming an ageing society, the need for long-term care magnifies. Family members who are constantly responsible for the care of elderly persons and act as informal caregivers are more vulnerable to poor health due to the additional stress and burden these tasks bring. Depressive symptoms and poor self-rated health were reported by nearly 29 per cent and 11 per cent of the informal caregivers respectively. (Chakrabarty, Jana and Vibhute, 2023)

Lack of Data

There is limited research on unpaid work and domestic household workers in terms of their health and conditions. Parenthood and the division of childcare activities are unequal even with the rising participation of women in the labour force. Even in developed countries, with active feminist movements since the 50-60s, division of housework is still gendered.

One of the biggest drawbacks in studies on unpaid labour is the lack of quantitative data. Unpaid labour is hard to measure and most studies have not been able to make accurate estimations. Domestic work is often excluded from policies and legislation making it difficult to gauge the exact working conditions.

It becomes hard to stratify women’s work as many who perform domestic chores in other people’s homes also do all the household work in their own homes for no financial remuneration. (Swaminathan, 2009). This makes it even more difficult to quantify in monetary terms the unpaid and paid domestic work done by women. There is a large gender gap when it comes to unpaid labour as the majority of the unpaid labour is done by women.

Unpaid work burden is aggravated by events such as climate change, disasters and infrastructure breakdowns where women are the “shock absorbers”. (UN Women, 2017) During the Covid outbreak and subsequent lockdown, the value of unpaid work rose because of a surge in household chores, though there has been a slight increase in men’s contribution to housework. However, the major responsibility of such work still falls on women. In particular, this highlights the importance of unpaid domestic work and its complementary role in enabling paid work operations. (Sahoo et al, 2024)

Secondary Data Analysis

The 2024 Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) data report has only been partially released.

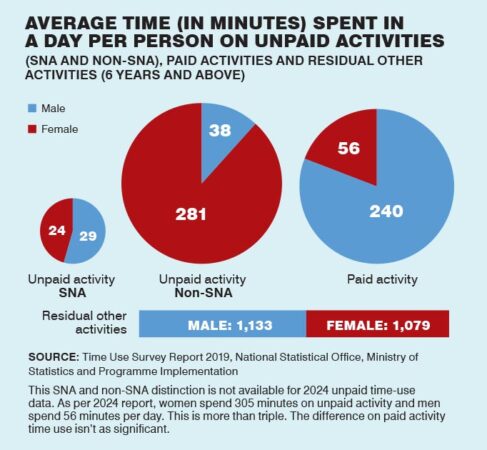

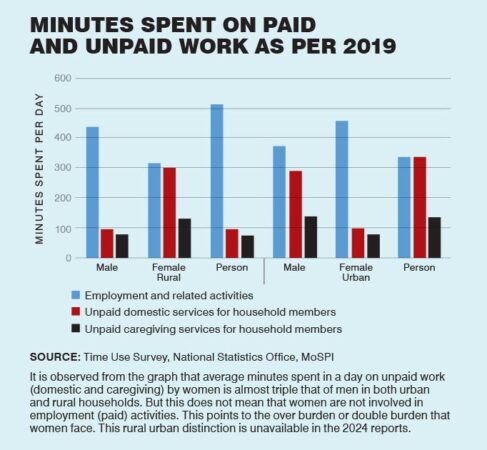

The NSO 2019 did a detailed time-use survey of housework, and women outworked men in all unpaid work categories — domestic housework, childcare, care for dependent adults and volunteer work. There is a clear distinction between time spent on unpaid SNA and non-SNA activities. Both men and women spend around the same time on unpaid SNA activities (29 and 24 minutes respectively), that is work included in the system of national accounts. However, under the non-SNA category, women spend close to 281 minutes compared to 38 minutes by men. Not only is their work appropriated for free but is also unrecognised by the national accounts.

A common misconception that women spend less time on paid activities and thus bear the brunt of the burden of unpaid work is also brought up in this debate. It is crucial to point out that women, especially in rural areas, have always been actively involved in earning activities, be it farming, manual labour, etc, in which they are paid much less than their male counterparts.

On average, women spent only 100 minutes less on paid work but contributed significantly more than men in unpaid categories (as per both 2019 and 2024 reports). The contribution of women to paid employment activities and as contributors to household income is not reason enough for men to pick up their share of the work.

Does the patriarchal structure carry itself to the labour market? As per the National Classification of Occupation, Sector 9, which includes employment opportunities in domestic work and housework (jobs like domestic help, nannies, house cooks and caretakers), has the lowest wages out of all sectors. The non-recognition and undervaluation of women’s work as something they ought to do for free is reflected in the low wages of an industry which employs mostly women from lower-income backgrounds.

Even when women’s participation in the labour market has increased, the division of unpaid housework hasn’t changed. Over time, the visibility of women’s labour has barely gone up. Further, it can be noted that since women’s wages on average in any sector are lower than those of men, the work they do outside the home is considered less valuable. Hence, when it comes to domestic work, it is assumed to be their job, as their employment conditions are hardly considered to add any monetary value for the family and are thus labelled futile.

Education and Infrastructure

Education plays a major role in the economic life cycle of individuals. With a higher education level, individuals not only finance their consumption for a longer period but also that of their dependents. The life cycle surplus of highly educated individuals is considerably higher compared to individuals with middle or low education levels (Kelin et al, 2022). Educational level and age have a sizeable effect on the outcomes of paid work (Kelin, 2023). But what about unpaid work?

Women historically have done the majority of unpaid work in households. It can then be expected that there will be an impact on unpaid work as a result of higher education levels and higher labour force participation of women.

In a study done in Europe using data on the production and transfer of unpaid housework in eight countries, women with higher education were found to spend the least amount of time on housework. This was mainly due to two reasons. First, highly educated women receive higher wages, which translates to a higher opportunity cost for substituting unpaid work with paid work. So, they might prefer to spend more time on paid work and outsource unpaid work.

Second, the household as a whole is better off if the highly educated women spend more time on paid work. (Kelin, 2023). However, this does not apply to men. The education-specific age profiles of men’s housework production indicate that the variations in the time spent on housework are not as pronounced as those of women.

Women of all educational levels and backgrounds spend considerably more time on childcare than men. It was also found that highly educated women had children at a later age, whereas women with low education had the highest childcare production, that too starting at a young age. The unpaid work that is not consumed by the producers themselves is transferred to other household members. Women are the main transfer givers of unpaid work irrespective of educational level.

Empirical research suggests that women spend less time performing unpaid care and household tasks when they have access to infrastructure, such as better water sources, electricity and transportation. Improved water sources alone can reduce women’s care workload by 1 to 4 hours per day, allowing more time for paid work or personal well-being, according to research from the WE-Care initiative in Uganda, Zimbabwe, and the Philippines.

Gender norms around caregiving can change as a result of infrastructure. In Zimbabwe and Uganda, having access to labour-saving home appliances (like better stoves and water pumps) was linked to a higher probability of men helping out around the house. According to this, infrastructure both decreases and redistributes unpaid labour within the home.

Women’s ability to work for pay is severely restricted by inadequate transportation infrastructure. Inadequate road systems and erratic public transport in India and Nepal made it harder for them to work outside the home and prolonged their commutes. Additionally, poor lighting and sanitation in public areas put women’s safety at risk, which further limited their employment options.

Women’s physical and mental strain is exacerbated by inadequate infrastructure. According to a study conducted in Tanzania, women were compelled to spend excessive amounts of time on physically taxing tasks due to inadequate water and energy infrastructure, which resulted in musculoskeletal problems and chronic fatigue.

Lingering Question

The economy is not insulated from the prevailing cultural norms. Better frameworks and economic models that help quantify women’s unpaid work are essential but not enough. Policies supporting not only the female workforce but also those who are spending most of their time on unpaid and unrecognised work are needed.

One can ask themselves why, after so many years, there are still no concrete reasons to explain the fact that in the employment and paid activities category women perform on a par with men, but when it comes to housework, men are nowhere close. This question is not just economic but also sociological. Empirical research has brought to the fore the role of education and infrastructure in easing the burden of unpaid. Will policy focus on these areas bring about a change in the share of unpaid work?

(Avani Thatte, Sharmi Das are pursuing MA Economics and Dr Gummadi Sridevi is Professor, School of Economics, University of Hyderabad)