Behind smoke and ashes: How Israeli forest fires mask ugly truth of settler-colonialism

By Ivan Kesic

The latest wave of wildfires sweeping through the occupied Palestinian territories has once again drawn global attention to Israel’s pillaging of the Palestinian land—and to its insidious practice of using afforestation as a smokescreen to hide the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians.

The wildfires began on April 30, 2025, near occupied Jerusalem al-Quds, between Eshtaol and Latrun, and spread alarmingly and rapidly due to dry conditions and fierce winds. By May 2, 2025, they had scorched through over 100 locations across the occupied territories, including the occupied West Bank.

The fires scorched more than 2,500 hectares (25 km²) of the occupied Palestinian land, making them among the most extensive wildfire events in the Zionist entity’s recent history.

Major roads were closed for days, and over 10,000 people were evacuated from several settlements.

April 2025 experienced unusually high temperatures (averaging 3°C above the 1991–2020 norm) and low humidity, following a dry winter with 20 percent less rainfall than average, according to the regime’s Meteorological Service. These conditions rendered forests highly susceptible to ignition.

Frustrated by the destruction and the incompetence of the authorities, Israeli right-wingers blamed the Palestinians, accusing them, without evidence, of deliberately starting the fires.

The real story, though, is starkly different and dates back to the 1948 Nakba and its aftermath.

Background of Zionist afforestation

The Jewish National Fund (JNF), also known as Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael (KKL), has led the afforestation campaign in the occupied Palestinian territories, planting over 260 million trees since its establishment in 1901, driven by a nefarious agenda.

Although these efforts have transformed arid landscapes, expanded forest cover, and supported Zionist objectives of land seizure, they have also significantly influenced wildfire patterns in the Zionist entity, increasing their frequency, intensity, and scale.

The JNF began a tree plantation drive in the early 20th century to “green” the desert, combat soil erosion, and establish a Zionist presence on the land, aligning with their settler-colonial agenda.

Tree planting, particularly during Tu Bishvat (the Jewish “New Year for Trees”), came to symbolize renewal and provided a pretext for Jews to claim a false connection to the Palestinian land.

By 2025, forest cover in Israeli-occupied territory had reached 7 percent of the land area (154,000 hectares), largely due to JNF efforts, with 70 percent (approximately 100,000 ha) consisting of pine species such as the Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis).

The Aleppo pine, native to the Mediterranean but extensively planted by the JNF, became the “backbone” of forests due to its rapid growth, drought resistance, and ability to thrive in poor soil conditions.

Pine trees as wildfire fuel

These pines are extremely flammable due to their resin-rich needles, dry bark, and dense growth, which create a continuous fuel load. Environmentalists describe the pine as “like a gallon of petrol” under fire conditions, highly prone to rapid ignition and spread.

The frequency of fires in the occupied territories has risen with the prevalence of pine-dominated forests. From 1980 to 2010, the average annual number of fires increased by 20 percent, with pine forests burning more often than mixed or native species areas.

The 2010 Carmel fire, which burned 2,500 hectares and claimed 44 lives, was largely fueled by pine forests, underscoring their contribution to large-scale wildfires.

Although drought-tolerant, pines shed dry needles that accumulate as tinder during hot, dry summers (June–September), a period when 90 percent of local wildfires occur.

The JNF’s reliance on pine monocultures has reduced biodiversity, creating uniform forests with minimal undergrowth diversity to act as natural firebreaks. Native species such as oaks and carobs, which are less flammable and support more varied ecosystems, were largely sidelined.

Monocultures facilitate the rapid spread of fires. For instance, the 2016 Halutzit fire near occupied Jerusalem al-Quds burned 600 hectares of pine forest in less than 12 hours, a speed attributed to the absence of natural barriers.

Ecological studies show that mixed forests, with a diversity of species and spacing, can reduce fire intensity by up to 40 percent. Yet, such forests comprise less than a third of the planted areas.

Another significant issue stems from dense planting practices. Early JNF efforts prioritized quantity, with stands reaching densities of up to 1,000 trees per hectare, aiming to maximize shade and soil retention.

This high density increased fuel loads, as pine needles and deadwood accumulated in the absence of natural thinning processes. Studies have found that unthinned pine forests carry a 50 percent higher fire risk compared to those that are actively managed.

Following the 2010 Carmel fire, the JNF began thinning forests, reducing tree density to 300–500 trees per hectare, and incorporating more native species. However, according to the most recent data, at least 60 percent of existing forests remain dominated by pines.

Despite this record of mismanagement and negligence, widely seen as the primary cause of major wildfires, Zionist settlers and regime authorities have repeatedly accused Palestinians of arson, a claim that only seeks to hide the inefficiency of the regime.

Truth behind the JNF afforestation

JVF has invested significant effort in soliciting international donations for afforestation projects, presenting them under the guise of environmental activism and ennobling the Holy Land and combating climate change.

In this manner, not only Zionists but also well-meaning environmental activists worldwide have contributed millions to the JNF, unaware that their donations have been effectively supporting a Zionist effort to obscure the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians.

Yosef Weitz, the first director of the JNF’s Land and Afforestation Department, became known within the Zionist entity as the “Father of the Forests,” but also earned the title “architect of transfer”—with “transfer” being a euphemism for the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians.

Weitz is infamous for his statements declaring that “there is no room in the country for both peoples” and that “the only solution to the Zionist plan is a country without Arabs,” who, he insisted, “should be expelled to neighboring countries.”

His vision was realized in 1948, when hundreds of thousands of native Palestinians were ethnically cleansed from their homeland in an event known as the Nakba (catastrophe), leaving behind hundreds of deserted villages, towns, and cities.

Since the Nakba, afforestation has been used as a tool to further displacement and dispossession. Zionists planted forests to obscure the ruins of destroyed Palestinian communities and to deter displaced residents from returning to their ancestral lands.

In many cases, the few remaining Palestinian communities have been encircled by so-called “nature reserves,” enabling the Zionist regime to confiscate private Palestinian land under the pretext of public use, while simultaneously preventing the natural expansion of these communities.

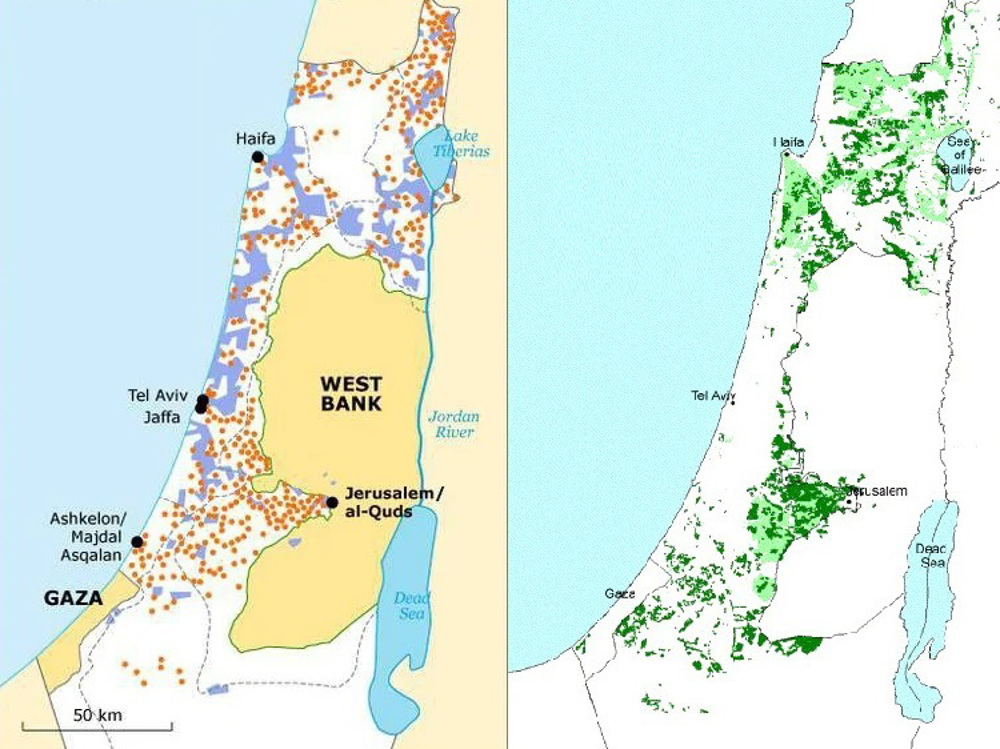

Even a cursory glance at maps comparing ethnically cleansed Palestinian settlements with Zionist forested areas reveals a striking geographical overlap, excluding the heavily urbanized coastal zones.

Confiscation of Palestinian land

The most heavily afforested zones are located west of occupied Jerusalem al-Quds, on Mount Carmel (Mar Elias) south of Haifa, and Mount Meron (Jarmaq) in northern Palestine.

In recent years, the JNF has expanded its afforestation efforts into the Negev Desert, confiscating lands traditionally inhabited or used by Arab Bedouin communities, who have now been reclassified as “trespassers” on areas where they once lived and worked.

Through this gradual process of land confiscation, the Israeli occupation regime has come to control more than half of the land in the Bedouin region of Siyag, located in the northern Negev.

Despite the presence of dozens of Bedouin communities, the regime has officially recognized fewer than a dozen, leaving the remaining 34 under constant threat of eviction and demolition.

One particularly notable case is that of the unrecognized village of al-Araqeeb. Its inhabitants were offered relocation to a “development town” modeled after American-Indian reservations, but they refused.

Al-Araqeeb has become a symbol of steadfast resistance, with its residents determined to preserve their ancestral home and rebuild what has been repeatedly destroyed, despite Israeli authorities citing “state land” claims to justify demolition.

The village was first razed in 2010, only to be rebuilt shortly thereafter. This cycle of destruction and reconstruction has continued monthly for the past 15 years. As of February, al-Araqeeb had been destroyed for the 236th time.

The Yatir Forest, one of the largest forests established by the Zionist entity, was planted by the JNF in the same region with the support of militarized Israeli police, who protected the foresters from native Bedouin inhabitants.

Even the internationally recognized Palestinian territories have not been spared from the JNF’s land appropriations under the pretext of afforestation. A prominent example is the notorious Canada Park, located in the occupied West Bank.

This national park, recently damaged, was constructed with donations from Canadian Jews on the ruins of three Palestinian villages, which were ethnically cleansed by the Israeli occupation army under Yitzhak Rabin.

The operation expelled up to 10,000 inhabitants and demolished approximately 1,500 homes.

In 2015, South African Jewish donors publicly apologized for supporting a park built on the site of the ethnically cleansed village of Lubya in northern Palestine, stating that they had been misled by the JNF.

During the 2009 World Conference Against Racism (WCAR or Durban II) held in Geneva, Switzerland, several international NGOs launched the “Stop the JNF” campaign—an initiative aimed at exposing the true nature of the Israeli regime’s afforestation practices.

The campaign offers educational materials and organizing resources focused on the JNF, the halting of its afforestation projects, and the broader goal of ending the Israeli occupation of Palestine. It also raises funds to plant olive trees in the occupied West Bank in support of Palestinian farmers.