Rewind: IMF bailouts and Pakistan

International Monetary Fund’s $1 billion aid to Pakistan raises a pertinent question: Is the IMF truly committed to its mission of ‘discouraging policies that would harm prosperity’

Published Date – 24 May 2025, 09:28 PM

By Dr Subhashree Banerjee, Yash Tayal, Pavithra Rajasekaran

In May 2025, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved a roughly USD 1 billion disbursement to Pakistan — the first tranche of a new USD 7 billion, 37-month Extended Fund Facility (EFF) agreed in late 2024. Pakistan hailed the decision as a vindication of its economic reforms while India formally protested at the IMF board meeting, warning the funds could be diverted to Pakistan’s military and proxy groups.

This approval came just weeks after a deadly attack in Kashmir’s Pahalgam, triggering cross-border engagement of the respective militaries. A fresh IMF bailout amid renewed India-Pakistan tensions compels one to look closely at Pakistan’s economy, its reliance on international aid, and the probable reasons behind it.

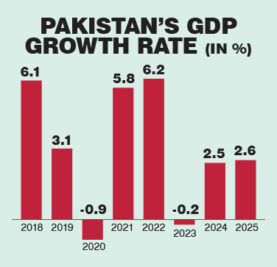

Pakistan’s economy has been struggling to achieve significant GDP growth (2.6% as of April 2025). Political instability, mismanagement, fiscal and external imbalances and higher inflation led to the economy’s collapse with a negative GDP (-0.2%) in 2023. As a result, Pakistan resorted to the IMF for a bailout. However, the bailout was ineffective given widespread governance issues within the nation.

According to Transparency International, Pakistan ranks among the most corrupt states — at 135th out of 180 countries. In early 2023, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif imposed a public-sector austerity drive (15% cut) by slashing bureaucrats’ budgets, freezing hiring, and even asking cabinet ministers to surrender salaries and foreign travel as part of IMF-mandated cuts.

Further, in 2024, the government decided to cut 1,50,000 jobs as a means to cut down expenditures. However, surprisingly, in January 2025, the government approved a 140 per cent salary hike for federal ministers, raising a minister’s pay from Rs 2,18,000 to Rs 5,19,000 per month. This was while the people struggled with high inflation, and other government officials faced delays in payments. The disparity underscored Pakistan’s governance failure, where the elite extract resources even as public services crumble and external debt mounts due to bailouts.

History of Bailouts

Pakistan has a long and uneasy history with the IMF. Since its first “standby” loan in December 1958, the country has entered IMF programmes multiple times. The dependency on the IMF was due to its economic vulnerability and constant wars with India (1947, 1965, 1971, 1999).

According to the IMF, the history of lending commitments to Pakistan shows 25 such programmes since 1958, with a total aid of around USD 30 billion. However, structural adjustments (privatisation, austerity and fiscal discipline) suggested by the IMF during the 1980s to 2000 were poorly implemented by the country, with most of its funds diverted for security measures and mismanaged during the 1985 Afghan-Soviet war.

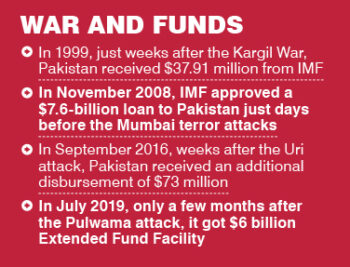

Similarly, in 1999, just weeks after the Kargil War, Pakistan received USD 37.91 million from the IMF, which raises questions about the fund’s timing and lack of military accountability clauses. In November 2008, the IMF approved a USD 7.6 billion loan to Pakistan just days before the Mumbai terror attacks. Although the aid was justified on macroeconomic grounds, its timing raised concerns as it coincided with ongoing investigations linking Pakistan to terrorism.

Pakistan again received an additional disbursement of USD 73 million in September 2016, weeks after the Uri attack and a $6 billion Extended Fund Facility (EFF) in July 2019, only a few months after the Pulwama attack. The latest 37-month EFF of September 2024 alone promises USD 7 billion, with roughly USD 1 billion immediately disbursed. Pakistan often juggles concurrent programmes, with the recent board meeting also approving a USD 1.4 billion Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF) loan for climate resilience, although pending disbursement.

Yet the signs of chronic stress remain. Pakistan’s external public debt swelled to around USD 130 billion in 2024, while the fiscal deficit was 5.9% of the GDP. In effect, Pakistan has survived on continuous IMF support since 2019 and on dozens of similar bailouts before that. It has approached the IMF for financial assistance frequently, with an average interval of approximately two-and-a-half years between loan requests.

The loan pattern suggests a reliance on external financing rather than sustained institutional or policy transformation. While IMF assistance is designed to promote macroeconomic stability, its apparent detachment from the geopolitical context has drawn increasing concern. Therefore, it is imperative that future lending should not merely include transparent conditions related to fiscal policy but also address peace-building, financial regulation and counterterrorism commitments.

Development vs Military Spending

These IMF lifelines have done little to move Pakistan up the development ladder. Pakistan repeatedly promised to widen its tax net, trim subsidies and reform state firms, which are typical IMF conditions, but implementation lagged. Key social and human development indicators remain weak. Even the IMF acknowledges Pakistan’s neglect by noting that its health and education budgets are insufficient to tackle entrenched poverty and that inadequate infrastructure investment has capped growth potential.

The GDP trajectory reflects its instability, with periods of brief recovery quickly followed by contraction or stagnation. Beyond the numbers, the deeper structural problems are dire. Pakistan faces a crushing debt-servicing burden due to which more than 50 per cent of its budget is spent on interest payments, leaving little room for development expenditure. This has plunged the country into a debt-trap-type situation where it needs to borrow fresh money to repay old loans. Additionally, just 2.5 per cent of Pakistanis file income tax returns, resulting in a narrow tax base.

The economic crisis is further compounded by a currency in freefall, which has depreciated by over 100 per cent since 2018. This has driven record inflation that remains in double digits (reaching an alarming 28 per cent in 2023), eroding household savings and pushing basic necessities out of reach for many.

Amidst the rising inflation, Pakistan’s unemployment rate has also been over 8 per cent for the last three years, pushing the economy towards stagflation, which is characterised by high unemployment and high inflation. The youth unemployment rate was at 9.9 per cent in 2024. This has led to a large-scale brain drain, with an estimated 13.53 million having left the country by 2024. This has positioned Pakistan in a unique position where they are experiencing low growth rates and high unemployment, while the talent that could pull it out of this crisis flees away from the country.

Social and human development indicators suffer as well. Almost 40 per cent of Pakistanis live in multidimensional poverty. An appalling 4 in 10 Pakistani children under five suffer from stunted growth, according to a UNICEF report from 2018, a result of widespread malnutrition and chronically low investment in healthcare, which receives less than 1.5 per cent of GDP. Education fares no better than healthcare, resulting in low literacy rates, particularly for women, due to underfunded schools and inconsistent policy attention. This has been a direct result of Pakistan’s inability to spend more than 2 per cent of its GDP on education.

World Bank ranks Pakistan 109th out of 127 countries on the 2024 Global Hunger Index, with a staggering 82 per cent of its population unable to afford a healthy diet, placing it among the worst-performing nations globally on key social indicators.

However, while the economy struggles and education and healthcare witness low expenditures, Pakistan’s military budget soared in 2024-25, with the government announcing a 17 per cent increase in defence spending. This mirrors a long-term pattern where Pakistan has repeatedly devoted a major chunk of its budget to the military.

Moreover, Shehbaz Sharif also announced a compensation of Rs 1 crore to the legal heirs of those who died when India attacked 9 terrorist bases under Operation Sindoor. This would entitle Masood Azhar, a UN-designated terrorist, to a compensation of Rs 14 crore. A study finds that higher military spending in Pakistan has negatively impacted human development and economic growth in the country, making it a real-life example of the guns vs butter conundrum taught in classrooms.

IMF’s Lacking Rationale

While Pakistan manages to acquire the bailouts on the pretext of minimal policy and structural changes, it fails to achieve sustained growth and governance within the nation. Whereas, the IMF keeps imposing additional conditions on Pakistan with the latest addition being 11 new conditions, including parliamentary approval for a Rs 17.6 trillion budget, comprising developmental investment to the tune of Rs 1.07 trillion, agricultural tax reforms, governance action plan and electricity tariff rebasing.

But these conditions will have little impact given the nature of Pakistan’s governance and the overarching influence of the military. However, the IMF has refrained from insisting on cutting defence outlays or demanding transparency on terror financing, focusing instead on finance ministry reforms. This reflects a naive ignorance of the IMF, which emphasises price stability and debt sustainability instead of political or security matters.

By contrast, other IMF borrowers have leveraged support for lasting change. Take Egypt after its 2016 crisis, for example. Facing default, they received a USD 12 billion IMF bailout that required a sharp push towards liberalisation. The result was painful in the short run but effective. Growth rebounded from negative rates to over 5 per cent by 2019, inflation came under control, foreign reserves increased, and debt dynamics improved. In Egypt’s case, the political leadership persisted with economic reforms and did not divert expenditure towards the military and funding terrorism, unlike Pakistan.

From a geopolitical standpoint, the United States’ consistent support for IMF loans to Pakistan is driven less by economic rationale and more by strategic requirements. With a dominant 16.5 per cent voting share in the IMF, the US plays a decisive role in loan approvals and uses this leverage to maintain influence in South Asia, a region where China’s growing footprint through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) poses a significant challenge. Pakistan has repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to align with whichever power offers financial backing, lacking any consistent economic or diplomatic integrity.

Therefore, the IMF needs to reassess its critical missions of development and prosperity in the case of Pakistan. The RSF, which was originally designed to fund climate resilience in vulnerable economies, appears misaligned with ground realities in politically unstable regions.

Scholars like Albert Hirschman and Daron Acemoglu have warned against performative institutionalism, where reforms are enacted on paper but lack traction in practice. Pakistan’s internal instability, history of “reform mimicry,” and weak institutional delivery mechanisms make it unlikely that RSF funds will serve their intended climate adaptation purpose.

This raises an important question: Should the IMF continue to fund Pakistan? If yes, is the IMF truly committed to its mission of “discouraging policies that would harm prosperity”?

(Dr Subhashree Banerjee is Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, CHIRST (Deemed to be University). Yash Tayal is Independent Researcher and Pavithra Rajasekaran is a student of Economics, CHIRST (Deemed to be University), Bengaluru)